Your feedback can help us improve and enhance our services to the public. Tell us what matters to you in our online Customer Satisfaction Survey.

If you are affected by any of the issues raised in this survey, help is available from the following national helplines or from local/regional helplines which you can find in the Background Notes.

Following a request from Government, the CSO has conducted the Sexual Violence Survey (SVS), in order to measure the prevalence of sexual violence in Ireland. The survey involves collecting information from respondents on their experience of sexual violence, as well as looking at the relationship of the perpetrator to the person who experienced sexual violence, and whether persons disclosed their experience of sexual violence to anyone. It also included a section on whether the person experienced sexual harassment in the last 12 months. The data collected will inform policy in several areas, including justice and equality, education, children, health and social service provision to those who experienced sexual violence. A pilot survey for the SVS was run in 2021 and the learnings from that pilot were incorporated into the survey design.

The legal basis for the collection of the survey was the Statistics Act 1993, Section 24, which outlines that CSO can ask persons to provide information to it on a voluntary basis.

Sexual violence is defined in this survey as a range of non-consensual experiences, from non-contact experiences to non-consensual sexual intercourse. The word “violence” as a term is sometimes associated with the use of force but it can also mean “having a marked or powerful effect” on someone, which includes actions or words that are intended to hurt people, as outlined in the Luxembourg Guidelines (a set of guidelines to harmonise terms on childhood sexual violence and abuse). Sexual violence is any sexual act which takes place without freely given consent or where someone forces or manipulates someone else into unwanted sexual activity. These experiences may range from a teenager making their friend watch a pornographic video on their phone, to someone being persuaded to undress or pose in a sexually suggestive way for photographs as a child, to a young woman being made to touch another person’s genitals without her consent or a man being threatened to have sex. This definition is based on national research, using the Scoping Group on Sexual Violence Data, and also on international research. The latter included the Istanbul convention, the methodological manual for the EU survey on gender-based violence against women and other forms of inter-personal violence (EU-GBV), the Luxembourg Guidelines and relevant research from the United Nations.

Sexual harassment is defined in this survey as unwanted behaviours that a person may have experienced in their daily life, which made the person feel offended, humiliated or intimidated. This was limited to events experienced in the last 12 months.

These behaviours include:

As above, this definition is based on national research, using the Scoping Group on Sexual Violence Data, and also on international research. Further detail can be found in the Definitions section.

In order for the data to be robust, explicit questions relating to sexual violence and harassment needed to be asked of some respondents. Conducting a survey dealing with highly sensitive issues involved designing a means of collecting data which addresses ethical considerations, as well as protecting the privacy of respondents and supporting survey staff in the field.

The Central Statistics Office (CSO) adheres to core values of Independence, Objectivity and Confidentiality as per the European Statistics Code of Practice. The underpinning legislation for the Office, the Statistics Act,1993, outlines the protection of confidential information (Section 21) which details the fact that information gathered will only be used for statistical purposes only, and that disclosure of information is prohibited by the Declaration of Secrecy which is signed by all staff and researchers. The Office operates in an ethical way overall but a survey on a sensitive issue like sexual violence introduces additional ethical responsibilities.

A CSO Social Statistics Ethics Advisory Group (SSEAG) was set up to provide advice to the CSO on the ethical aspects of the conduct of the surveys which may require such oversight and the SVS was the first survey they reviewed. The terms of reference and membership of this group can be seen on the CSO website.

As part of the initial stages of building expertise on the survey topic, international approaches to data collection on sexual violence were appraised by the CSO. Where there was little information on data collection specifically on sexual violence, related topics which could be deemed as sensitive were examined instead, for example, violence against women, domestic violence and gender-based violence.

A key reference used by many organisations (United Nations, Eurostat, academic papers) is the 2001 publication by the World Health Organisation (WHO) - Putting Women First: Ethical and Safety recommendations for Research on Violence against Women. This document was created as part of development work for the WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence Against Women. It summarises ethical and safety concerns related to population-based surveys on domestic violence against women. The document itself states that “many of the principles identified are also applicable to other forms of quantitative and qualitative research on this issue”.

The principles are outlined here:

These principles were also noted in a 2014 UN document on data collection as remaining widely accepted principles for such research.

Submissions which outlined the steps taken by the CSO to meet its ethical responsibilities when conducting the pilot and main survey of the Sexual Violence Survey were prepared and shared with the Group. It outlined how well-established international principles for the conduct of sensitive surveys such as a sexual violence survey had been applied by CSO to ensure the ethical conduct of the survey.

The CSO SSEAG reviewed the submissions and offered advice on the methodology proposed. This advice was considered by the Office, accepted and incorporated where feasible into the survey design.

The SVS was a newly designed questionnaire which used the 2002 Sexual Abuse and Violence in Ireland (SAVI) report and the European Gender-Based Violence (EU-GBV) survey, as well as other international surveys, as reference points when designing the questions.

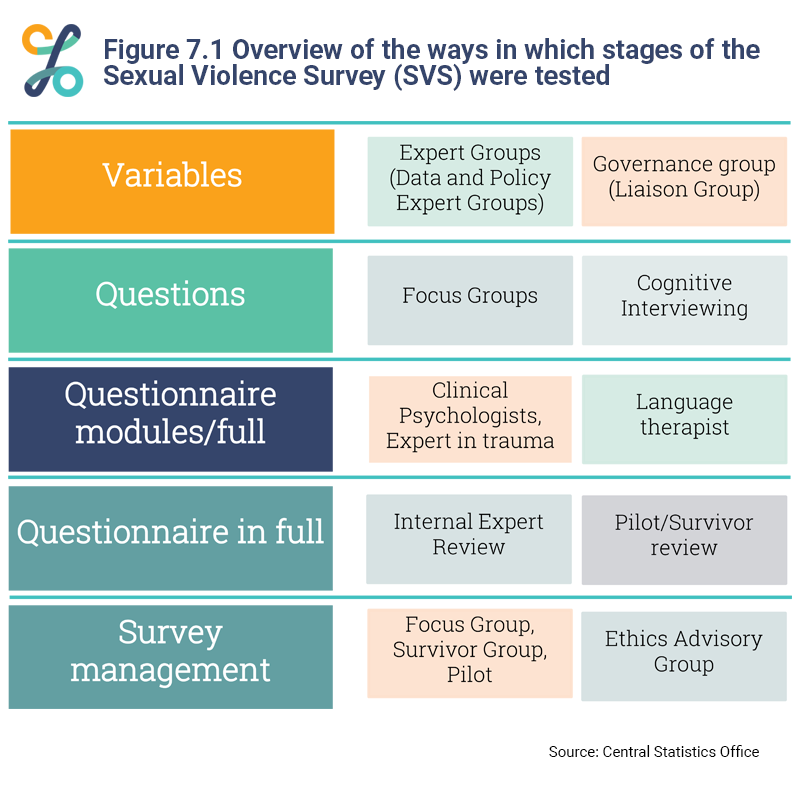

Due to the novel nature of the survey, significant testing was conducted on the concepts and questions which is outlined in Figure 7.1. Further detail on the work completed as part of questionnaire design is available in Appendix I.

[Figure 7.1 Image Description]

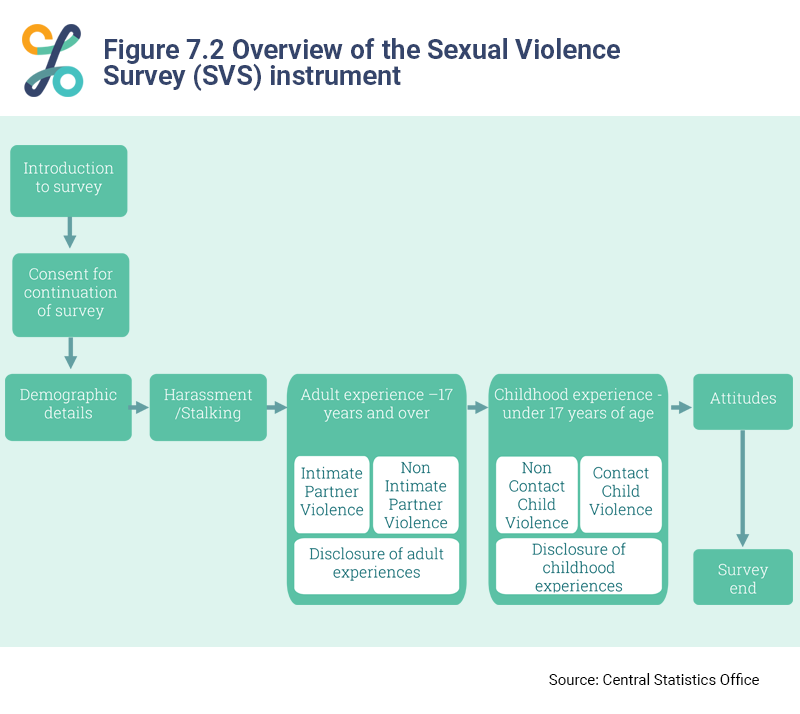

Overall, the SVS questionnaire can be broken down into these sections:

The flow of the questionnaire is summarised in Figure 7.2. The questionnaire itself can be found on the Methods page on the CSO website.

[Figure 7.2 Image Description]

The SVS was collected directly from private individuals, aged 18 and over who were resident in Ireland.

The sample was selected from the Irish Population Estimates from Administrative Data Source (IPEADS) person-based sampling frame. IPEADS uses pseudonymised administrative data from public sector bodies to produce estimates of the population in Ireland and includes breakdowns by several variables including sex, age, nationality, marital status and economic status. IPEADS is created using 17 different data flow sources, such as the Central Record System (CRS), the Local Property Tax (LPT), etc., and consists of 5.2 million person records. This was updated with information from Census to quality check and ensure the most up to date view of those resident in Ireland as of the 1 January 2022.

Due to this person-based frame, a simple random sample stratified by local authority area was generated. A sample of 12,665 was chosen.

The survey to collect the information for this publication began in May 2022 and it ran until December 2022.

The questionnaire asked questions about lifetime experiences of unwanted or non-consensual sexual activity. It also asked questions about sexual harassment for the reference period of twelve months prior to the interview taking place.

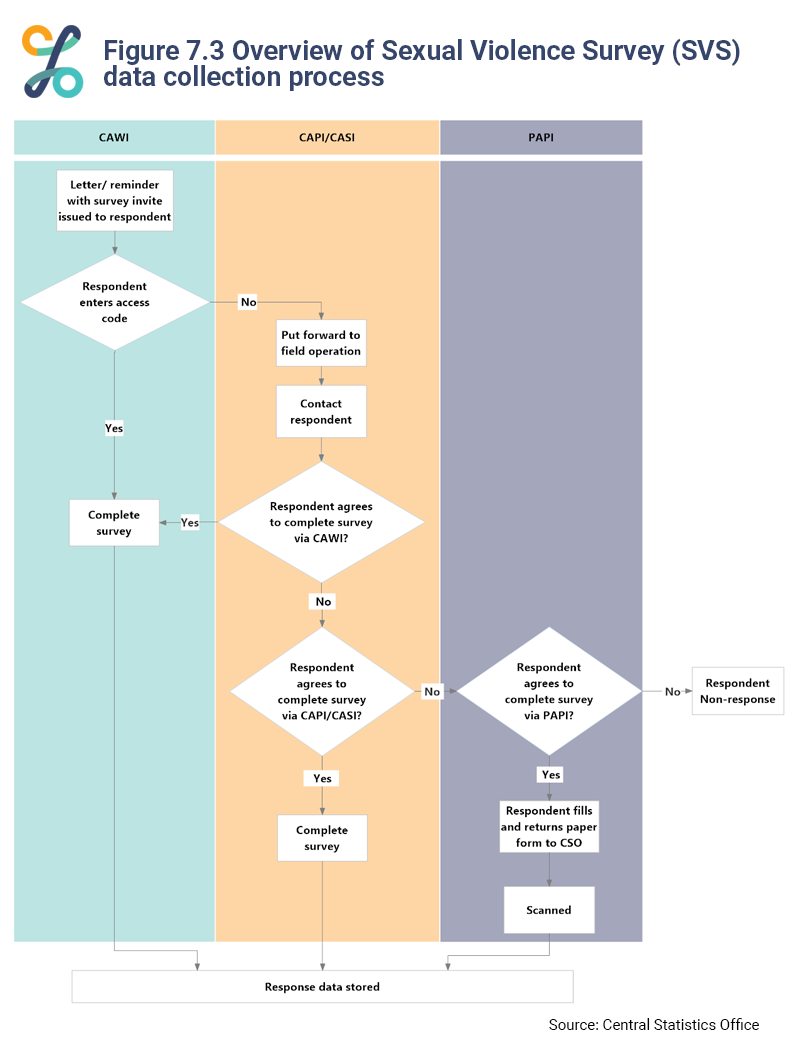

The data for the survey was collected between May and December 2022. To ensure our ethical responsibilities to respondents who may have been in an ongoing abusive relationship, the survey was known as the ‘Safety of the Person’ survey during the data collection phase. Ethical considerations also led to the decision to have a graduated and less explicit introduction to the survey. After this initial introduction, before the respondent began the main part of the survey, they were informed clearly about the nature of the survey and their consent was sought before they could proceed through to the survey questionnaire. To ensure that a wide range of respondents could engage with the survey, a range of data collection modes was used: secure web-form, face-to-face with a confidential element for the sensitive questions, and a paper form. The vast majority of respondents replied via the secure web-form.

The initial contact with the selected respondent was led by the Field Administration Unit (FAU) in the CSO. Letters of invitation were addressed directly to the selected respondent. Within the letter was the survey link and the authentication code to access the online survey. Up to two reminders were issued to the selected respondent if there was no response. If no response had been received, then the case was forwarded to the field data collection team (25 interviewers and 3 co-ordinators).

The field data collection followed the standard model for data collection in the Office. If any respondent contacted the Office directly instead, relevant information was passed where necessary to the interviewer as per normal procedures. The field data collection team were provided with training and interview material in advance and were comfortable with using the required technology.

Training for this included:

At the first visit, interviewers encouraged respondents to go online to complete the survey. If a respondent requested the survey link or authentication code, then the Office reissued the survey invite letter to the respondent.

If the respondent did not complete the survey online, the interviewer revisited the respondent and offered a tablet-based interview with the respondent completing the entire survey on the interviewer tablet. If the respondent was not able to complete the survey on the tablet but wished to contribute to the survey, a paper form was offered as an alternative.

The process is summarised in Figure 7.3.

To encourage and assist respondents that have experienced sexual violence to disclose often difficult and painful experiences in a survey setting, the mode of data collection is important. Research shows that if under-reporting of instances of sexual violence is not managed then it will lead to biased results. Tourangeau and Yan (2007) state that the biases introduced through under-reporting of instances of sexual violence will far exceed all other forms of survey and sampling errors.

According to van Wijk et al. (2015), disclosure of sexual violence shows more susceptibility to mode effects than disclosures of physical violence. Similarly, Tourangeau and Yan (2007) advise that studies going back nearly 50 years suggest that respondents are more willing to report sensitive information when the answers are self-administered than when they are administered by an interviewer.

In order to ensure data quality and respondent safety, the SVS survey was completed without the assistance of an interviewer. It created an environment of privacy for the respondent to answer honestly and without any potential perceived judgement. This approach is preserved for all mode choices offered to the respondent. Ways in which underreporting through the survey and respondent distress were managed is listed in Appendix II and III.

The number of responses for the SVS was 4,575 responses. This represents a 36% response rate based on the 12,665 individuals who were in the original sample This compares very favourably with similar surveys conducted internationally (see section below). As with all surveys, there is the potential for bias in the survey responses (where different cohorts of the population have a different propensity to respond to the survey). With the SVS there are two particular areas where non-response bias could be introduced into the survey:

The following mitigated the risks around non-response:

In conjunction with CSO Methodology Division, two additional methods of non-response adjustment were considered:

There are practical considerations for such a survey – for example, would someone who previously didn’t respond to the survey now engage in a non-response survey, but fundamentally, for ethical considerations, such a non-response survey is not possible. It would involve direct recontact with respondents and non-respondents. Persons who didn’t respond to the main survey may not have responded for valid safety considerations (for example they may be in an ongoing abusive relationship), and those who did respond may have done so in a very confidential manner within their household (with any recontact of that respondent potentially causing a safety issue also). With the ethical consideration of ‘do no harm’ determining our approach to survey operations, it is not possible to conduct such a non-response survey.

This methodology is not possible to implement. To provide added reassurance to respondents around the confidentiality of their data, personal identifiers on the frame used for sample selection and post-out were irrevocably removed from CSO databases once survey contact was made with the respondent and their data received by CSO. This breaking of the link between population frame and sample for sound ethical considerations means that the auxiliary demographic variables cannot be attached to the sample.

The general international experience for surveys of this nature is that non-response bias adjustment is not done, given the substantive ethical issues involved in such an exercise.

The following table highlights the respective response rates for similar type surveys conducted internationally. Differences in survey modes, questions asked, and target populations can have a marked impact on response rates and so caution should be exercised in examining this table. International comparison of sexual violence response rates and prevalence levels is difficult, but this table provides an indication of the response rate for the SVS as compared to international surveys of a similar type.

| Country | Survey Title | Mode | Response Rate |

| The Netherlands | Feeling Safe and Being Safe | Web based | 28% |

| Austria | Quality of Life and Security in Austria | Face to face with self-completion/ Web based | 28-42% |

| Slovenia | National Safety Survey | Web based / Face to face/ Telephone | 49% |

| Canada | Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces | Telephone/ Web based | 43% |

| USA | The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey | Telephone | 8% |

The EU survey on gender-based violence against women and other forms of inter-personal violence (EU-GBV) which is being conducted in 18 EU countries currently, has developed a comprehensive methodological manual for those countries conducting the survey. While it does not advise a specific non-response adjustment approach, it encourages countries to get the highest response rate possible with advice on how to build this into the preparatory stages of the survey development process, e.g. advance letters, neutral name, experienced interviewers, good training delivered, active monitoring during data collection and address any drops in response rate when they happen, etc. CSO have implemented this advice in the survey management for this survey and the weighting and calibration done for the survey estimates are adjusted for non-response as far as possible and aligned to the population totals.

Once the data was back in the CSO it was checked. After the data collection phase was complete, the data was aggregated together. Occupation text strings were re-coded to the proper category while further validation checks were done.

To provide national population results, the survey results were weighted to represent the entire population of persons aged 18 years and over. The survey results were weighted to agree with population estimates broken down by age group, sex and region and were also calibrated to highest level of education achieved totals.

Individual weights were calculated for all responses in the initial weighting scheme. This eliminated the bias introduced by discrepancies caused by non-response, particularly critical when the non-responding households are different from the responding ones in respect to some survey variables as this may create substantial bias in the estimates.

To obtain the final weights for the results, after the previous steps were carried out, the distribution of households by sex and age and highest level of education achieved was calibrated to the population of households in Quarter 4 2022. The CALMAR2-macro, developed by INSEE, was used for this purpose.

Overall prevalence estimates by selected demographic characteristics were calculated along with 95% confidence intervals and published in the Background Notes of the Sexual Violence Survey 2022 - Main Results publication.

Estimates for number of persons where there are less than 30 persons in a cell are too small to be considered reliable. These estimates are presented with an asterisk (*) in the relevant tables.

Where there are 30-49 persons in a cell, estimates are considered to have a wider margin of error and should be treated with caution. These cells are presented with parentheses [ ].

In the case of rates, these limits apply to the denominator used in generating the rate.

All data from surveys are subject to sampling and other survey errors, which are relatively greater in respect of smaller values.

The sum of row or column percentages in the tables in this report may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

Sexual harassment is defined by unwanted behaviours that a person may have experienced in their daily life, which made the person feel offended, humiliated or intimidated. This was limited to those experienced in the last 12 months.

These behaviours include:

Please note that as the survey ran from May to December 2022 that the 12-month period spans May 2021 to December 2022 depending on when the respondent completed the survey. This period did include varying levels of COVID-19 restrictions both nationally and internationally.

Sexual harassment is defined by various unwanted behaviours which happened in a person’s daily life. The components of this are:

The respondent was asked to think about unwanted experiences that may have happened in the last 12 months when answering the question. The question used to capture this was:

...has anyone made crude or sexually explicit remarks to you that you found offensive, humiliating or intimidating while you were online (including social media, dating apps, discussion boards)?

The respondent was asked to think about unwanted experiences that may have happened in the last 12 months when answering the question. The question used to capture this followed on from the question on “Remarks of a sexual nature online” and the question asked was:

...has anyone made crude or sexually explicit remarks to you that you found offensive, humiliating or intimidating while you were in any other situation e.g. in person, by text, phone call?

The respondent was asked to think about unwanted experiences that may have happened in the last 12 months when answering the question. The variable captures cases where a person had private sexual images or videos of themselves shared without their permission. The question used to capture this was:

...has anyone shared private sexual images or videos of you without your permission?

An additional note on historic images (those older than 12 months) was included at the end of the question. It stated “Please include cases where you only became aware of historical images being shared without your permission if they were shared within the last 12 months”.

The respondent was asked to think about unwanted experiences that may have happened in the last 12 months when answering the question. The question used to capture this was:

...has anyone exposed themselves physically to you in a way that made you feel uncomfortable?

The respondent was asked to think about unwanted experiences that may have happened in the last 12 months when answering the question. The question used to capture this was:

...have you experienced any of the following behaviours in your daily life, for example, in a public place, at home or at work...

...exposure to sexually explicit pictures or photos that made you feel offended, humiliated or intimidated?

The respondent was asked to think about unwanted experiences that may have happened in the last 12 months when answering the question. The question used to capture this was:

...have you experienced any of the following behaviours in your daily life, for example, in a public place, at home or at work...

...physical contact, for example, touching, hugging or being in close proximity that made you feel offended, humiliated or intimidated?

The respondent was asked to think about unwanted experiences that may have happened in the last 12 months when answering the question. The question used to capture this was:

...have you experienced any of the following behaviours in your daily life, for example, in a public place, at home or at work...

...inappropriate sexual advances that made you feel offended, humiliated or intimidated?

The respondent was asked to think about unwanted experiences that may have happened in the last 12 months when answering the question. The question used to capture this was:

...have you experienced any of the following behaviours in your daily life, for example, in a public place, at home or at work...

...any other sexually inappropriate behaviour that made you feel offended, humiliated or intimidated?

The respondent was asked how often they experienced these various types of sexual harassment behaviours in the survey. Each of these non-consensual behaviours could be experienced in a single incident, event, relationship or across several incidents, events, relationships.

In the case where someone selected one behaviour only, how often this was experienced in the last 12 months was captured with this question:

You have indicated that you experienced one of these types of unwanted behaviour.

How often did you experience this in the last 12 months?

Please select one of the following

If there were multiple experiences of sexual harassment shared in the survey, the person was asked to share details on the experience that affected the person the most. In the case where someone selected more than one behaviour, this is how the frequency was captured:

You have indicated that you experienced more than one of these types of unwanted behaviour.

Thinking about the experience that affected you most, how often did this happen to you in the last 12 months?

Please select one of the following

The perpetrator is the person that carried out the sexual harassment experience against the respondent. Personally identifiable information on the perpetrator was not sought in the survey. The sex of the perpetrator was captured in the detailed section of the questionnaire. If there were multiple experiences of sexual harassment shared in the survey, the person was asked to share details on the experience that affected the person the most. Respondents who shared that the sexual harassment experience involved more than one person were not asked to give the sex of the perpetrators.

For those who shared sexual harassment experiences in the survey, this was the question used to capture this:

Was the person that did this to you...

Please select one of the following

The perpetrator is the person that carried out the sexual harassment experience against the respondent. Personally identifiable information on the perpetrator was not sought in the survey. The general relationship to the perpetrator was captured in the detailed section of the questionnaire. If there were multiple experiences of sexual harassment shared in the survey, the person was asked to share details on the experience that affected the person the most. Respondents who shared that the sexual harassment experience involved more than one person were not asked the relationship question.

For those who shared sexual harassment experiences in the survey, this was the question used to capture this:

At the time, was the person that did this to you...

Please select one of the following

For those who shared sexual harassment experiences, this was the question used to capture this:

Where did it happen?

Please select all that apply

Disclosure is defined as the person told anyone about an experience of sexual harassment. People may have experienced sexual harassment in one sexual harassment episode or in many episodes. If there were multiple experiences, the person was asked to share details on the experience that affected them the most.

For those who experienced sexual harassment, this was the question used to capture this:

Did you disclose to anyone what happened to you?

Please select one of the following

Please note that in the case where a respondent selected more than one type of sexual harassment experience, the format of question does not facilitate the assignment of the type of experience to the disclosure.

The type of individual the person disclosed a sexual harassment experience to was captured in the survey.

For those who did disclose a sexual harassment experience, this was the question used to capture this:

Did you disclose to any of the following?

Please select all that apply

Stalking means persistent, unwanted actions like following you, waiting for you, contacting you by phone, text and/or social media, that are against your wishes or imply threats. This survey was specific to the topic of sexual violence. As stalking involves a wider scope of unwanted behaviours incorporating potential elements of domestic violence or coercive control, the question on stalking focuses on where a person feared that they were at risk of sexual violence. Hence this variable is described as stalking with fear of sexual violence.

This was limited to experiences which occurred in the last 12 months.

Please note that as the survey ran from May to December 2022 that the 12-month period spans May 2021 to December 2022 depending on when the respondent completed the survey. This period did include varying levels of COVID-19 restrictions both nationally and internationally.

For all respondents, this was the question used to capture this:

Thinking about the last 12 months...

...has anyone stalked you in a way that made you fear that you were at risk of sexual violence?

(Stalking means persistent, unwanted actions like following you, waiting for you, contacting you by phone, text and/or social media, that are against your wishes or imply threats)

Please select one of the following

The perpetrator is the person that carried out the particular stalking with fear of sexual violence experience against the respondent. The number of perpetrators in the last 12 months was captured in the detailed section of the survey and used the same question as the sex of the perpetrator.

For those who shared stalking with fear of sexual violence experiences in the survey, this was the question used to capture this:

Was the person that did this to you...

Please select one of the following

The perpetrator is the person that carried out the particular stalking with fear of sexual violence experience against the respondent. Personally identifiable information on the perpetrator was not sought in the survey. The sex of the perpetrator was captured in the detailed section of the questionnaire. Respondents who shared that the sexual harassment experience involved more than one person were not asked to give the sex of the perpetrators.

For those who shared stalking with fear of sexual violence experiences in the survey, this was the question used to capture this:

Was the person that did this to you...

Please select one of the following

The perpetrator is the person that carried out the particular stalking with fear of sexual violence experience against the respondent. Personally identifiable information on the perpetrator was not sought in the survey. The general relationship to the perpetrator was captured in the detailed section of the questionnaire. Respondents who shared that the sexual harassment experience involved more than one person were not asked the relationship question.

For those who shared stalking with fear of sexual violence experiences in the last 12 months in the survey, this was the question used to capture this:

At the time, was the person that did this to you...

Please select one of the following

Disclosure is defined as the person told anyone about an experience of stalking with fear of sexual violence. For those who experienced stalking with fear of sexual violence, this was the question used to capture this:

Did you disclose to anyone what happened to you?

Please select one of the following

Please note that in the case where a respondent selected more than one type of sexual harassment experience, the format of question does not facilitate the assignment of the type of experience to the disclosure.

The type of individual the person disclosed a stalking with fear of sexual violence experience to was captured in the survey.

For those who did disclose a stalking with fear of sexual violence experience, this was the question used to capture this:

Did you disclose to any of the following people?

Please select all that apply

Respondents were asked their age directly. The survey was only asked of persons aged 18 or over. Age groups were classified as follows:

Tables where the age classification are grouped together, for example, 55 and over, are provided in order to provide reliable estimates for that category.

This classification is derived from a single question and refers to educational standards that have been attained and can be compared in some measurable way and the question is included in the Census.

The question is phrased as follows:

What is the highest level of education or training you have attained?

The responses from the respondents were then coded to the following educational levels:

The Principal Economic Status (PES) classification is based on a single question in which respondents are asked what is their usual situation regarding employment and given the following response categories:

This classification followed the Census question approach. Respondents were asked: What is your ethnic group/background? The responses were categorised as follows:

Due to the sensitivity of the survey, free text fields were not permissible in general so there was no free text field for the other category.

The sexual orientation classification is based on a question taken from the Q1 2019 Equality and Discrimination Survey.

The question is phrased as follows:

Which of the following options best describes how you think of yourself?

Please note in the publication where we state, for example, bisexual people, we mean those who identify as bisexual at the point when the survey was collected. Or where we state heterosexual in a table, we mean those who identify as heterosexual / straight at the point when the survey was collected.

This classification followed the Census question approach. Respondents are classified as having a disability if they indicate that they have any of the long-lasting conditions or difficulties listed in the following question:

Do you have any of the following long-lasting conditions or difficulties?

This classification followed the usual LFS question approach. Respondents are classified accordingly when they respond in the following question:

Which of the following categories describes your current marital status?

The married classification in the tables includes those who responded that they were married or in a civil partnership.

This classification followed the usual LFS question approach. Respondents are classified accordingly when they respond in the following question:

Are you an Irish citizen?

The Sexual Violence Survey will be published as a series of publications over the course of several weeks. While the final titles for the publications are to be agreed, the publications will concentrate on the following areas:

This will include information, by sex and age, on overall prevalence level for lifetime adulthood and childhood experiences of sexual violence, by type of sexual violence experience (contact, non-contact, etc.), as well as the overlap between child and adult sexual violence experiences. it will also include data on the relationship with the perpetrator and whether the person disclosed their experience of sexual violence to anyone (by adult and child experience).

This will include information on partner and non-partner experiences as well as the occurence of experiences, who was involved, and if non-partner experiences, the location of the sexual violence experience. It also will present on the detailed sociodemographic characteristics (sexual violence by educational attainment, sexual orientation, nationality, etc.)

This will include information on contact and non-contact experiences, as well as the ocurence of experiences, who was involved, the location of the experience and the respondent’s view on the reason why it stopped. It also will present on the detailed sociodemographic characteristics (sexual violence by educational attainment, sexual orientation, nationality, etc.)

This will include information broken down by adult and childhood experiences as well as who was told, how long it took to do so, the reasons why the person disclosed or not, whether the person disclosed to the gardai and/or if they used any services e.g. medical, counselling, etc.

This will include information on sexual harassment and stalking events that occurred in the last 12 months. It will look at the type of harassment experienced, the frequency of the experience, who did it, and whether it was disclosed.

This will include information based on responses from those who did not disclose any experiences of sexual harassment or sexual violence in the survey. It will contain information on the opinion of the respondents who were not victims of sexual violence on several so-called ‘rape myths’ surrounding sexual violence and the perception of the frequency of sexual violence in the community.

The following should be considered when attempting to compare the results of this survey with the results of other countries/other surveys:

If you are affected by any of the issues raised in this publication, help is available at from the following organisations.

| County | Service | Helpline | Office | Website |

| Carlow | Carlow & South Leinster Rape Crisis Centre | 1800 727 737 | (059) 913 3344 | www.carlowrapecrisis.ie |

| Cavan | Sligo Rape Crisis Centre | 1800 750 780 | (071) 91 71188 | www.srcc.ie |

| Clare | Rape Crisis Midwest | 1800 311 511 | (065) 686 4665 | www.rapecrisis.ie |

| Cork | Sexual Violence Centre Cork | 1800 496 496 | (021) 450 5577 | www.sexualviolence.ie |

| Donegal | Donegal Sexual Abuse and Rape Crisis Centre | 1800 44 88 44 | (074) 912 8211 | www.donegalrapecrisis.ie |

| Dublin | Dublin Rape Crisis Centre | 1800 77 88 88 | (01) 661 4911 | www.drcc.ie |

| Galway | Galway Rape Crisis Centre | 1800 355 355 | (091) 564 800 | www.galwayrcc.org |

| Kerry | Kerry Rape and Sexual Abuse Centre | 1800 633 333 | (066) 712 3122 | www.krsac.com |

| Kildare | Carlow & South Leinster Rape Crisis Centre | 1800 727 737 | (059) 913 3344 | www.carlowrapecrisis.ie |

| Kilkenny | KASA/Kilkenny Rape Crisis Centre | 1800 478 478 | (056) 775 1555 | www.kasa.ie |

| Laois | Tullamore Sexual Abuse & Rape Crisis Counselling Service | 1800 32 32 32 | (057) 932 2500 | www.tullamorerapecrisis.ie |

| Leitrim | Sligo Rape Crisis Centre | 1800 750 780 | (071) 91 71188 | www.srcc.ie |

| Limerick | Rape Crisis Midwest | 1800 311 511 | (061) 311 511 | www.rapecrisis.ie |

| Longford | Athlone Midlands Rape Crisis Centre | 1800 306 600 | (090) 64 73862 | www.amrcc.ie |

| Louth | Rape Crisis and Sexual Abuse Centre (North East) | 1800 21 21 22 | (042) 933 9491 | www.rcne.ie |

| Mayo | Mayo Rape Crisis Centre | 1800 234 900 | www.mrcc.ie | |

| Meath | Dublin Rape Crisis Centre | 1800 77 88 88 | (01) 661 4911 | www.drcc.ie |

| Monaghan | Rape Crisis and Sexual Abuse Centre (North East) | 1800 21 21 22 | (042) 933 9491 | www.rcne.ie |

| Offaly | Tullamore Sexual Abuse & Rape Crisis Counselling Service | 1800 32 32 32 | (057) 932 2500 | www.tullamorerapecrisis.ie |

| Roscommon | Athlone Midlands Rape Crisis Centre | 1800 306 600 | (090) 64 73862 | www.amrcc.ie |

| Sligo | Sligo Rape Crisis Centre | 1800 750 780 | (071) 91 71189 | www.srcc.ie |

| Tipperary | Tipperary Rape Crisis and Counselling Centre | 1800 340 340 | (052) 6127676 | www.trcc.ie |

| Waterford | Waterford Rape & Sexual Abuse Centre | 1800 296 296 | (051) 873362 | www.waterfordsac.ie |

| Westmeath | Athlone Midlands Rape Crisis Centre | 1800 306 600 | (090) 64 73862 | www.amrcc.ie |

| Wexford | Wexford Rape and Sexual Abuse Support Services | 1800 33 00 33 | (053) 9122722 | www.wexfordrapecrisis.com |

| Wicklow | Dublin Rape Crisis Centre | 1800 77 88 88 | (01) 661 4911 | www.drcc.ie |

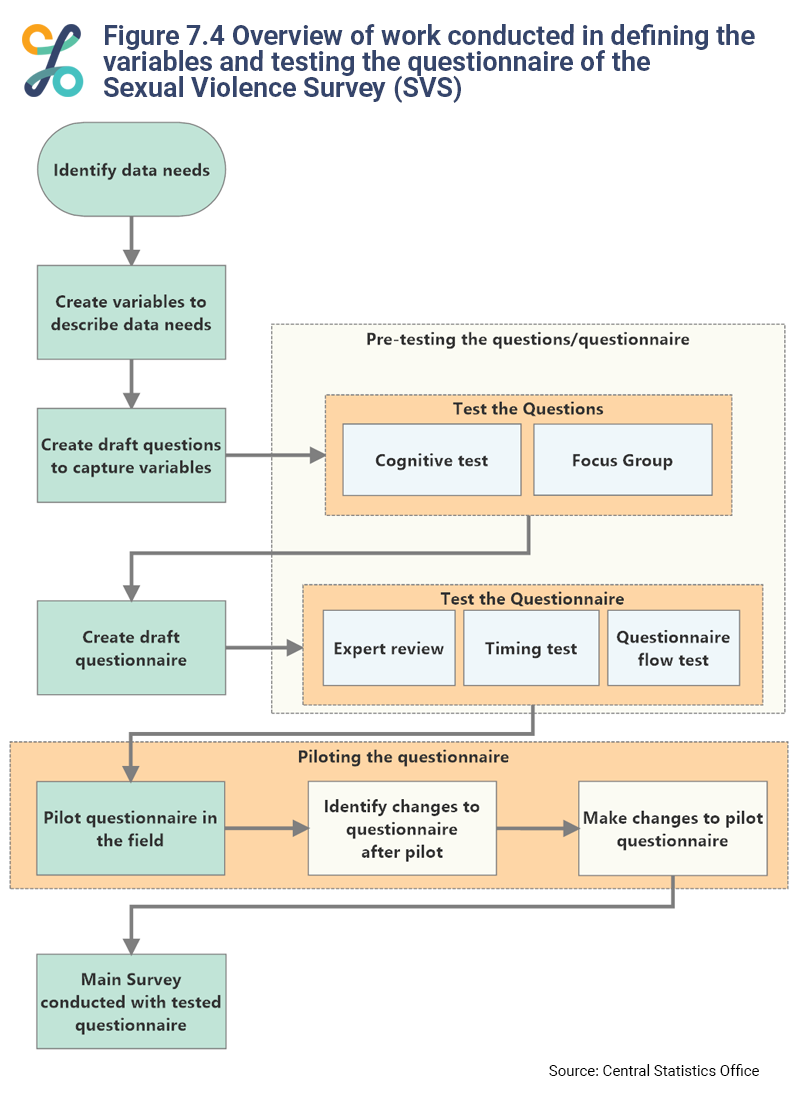

The outline of work conducted in defining the variables and testing the questionnaire is summarised in Figure 7.4 below.

[Figure 7.4 Image Description]

Identifying data needs was addressed through using the data list provided as part of the Scoping Group Report on Sexual Violence data. Data experts and policy experts were identified and consulted on the definition of the data points provided, discussed prioritisation and core needs for policy/service development.

Following this a variable list was created and shared with the SVS Liaison Group and Steering Group where feedback, where appropriate, was incorporated.

Questions were designed to capture these variables using various reference points for crafting the questions, for example, Eurostat Gender Based Violence Survey, The Sexual Assault and Violence in Ireland report (SAVI), Scottish Crime and Justice Survey, Crime Survey of England and Wales, model UN questionnaire, etc.

A process of testing these questions was designed using best practice techniques. The two main methods were cognitive testing and focus groups. In summary:

Due to the sensitivity of the topic, the questions were split into sensitive and non-sensitive questions. The non-sensitive set of questions were asked of the volunteers from within the Office and the sensitive set of questions were posed to service providers volunteers who would be more familiar with the language and be better equipped to handle the potential distress caused by these sensitive questions. In all, there were ten interviews conducted.

Due to the sensitivity of the topic, we have chosen to use service providers rather than volunteers from the Office for the discussion to facilitate the voice of victims through this format rather than a one-on-one format in the cognitive test. In all, two focus groups were conducted.

Once conducted a report was drawn up and learnings were incorporated into the questionnaire.

Evaluating the whole draft questionnaire was conducted both before the pilot was run (April to June 2021) and the pilot itself was a test of the questionnaire. An overview is provided below:

A concurrent focus group was held with those who experienced sexual violence during the pilot to get qualitative feedback. It identified some areas for additional work to be completed for the questionnaire, such as including ways to signal progression through the questionnaire and improving the format of some questions (particularly the disability and consent questions).

The collection of data on sexual violence involved the use of sensitive questions. Sensitive questions are identified by Tourange and Lee as those which display some of the following characteristics:

The impact of this is higher non-response rates, both in terms of unit and item non-response. Unit non-response occurs when a respondent refuses to participate in the survey; item non-response occurs when respondents do not answer particular questions in the survey.

This can lead to a biased measurement and is a particular issue for sexual violence measurement. The reasons for this apparent bias in the measurement of the prevalence of sexual violence in surveys are varied. Notwithstanding media reports of specific or alleged crimes involving sexual violence, the topic itself is generally not part of everyday conversation. It may provoke feelings of unease, nervousness and awkwardness in those who are not used to speaking openly about the topic or using that specific language. For those who have direct or indirect experience of harassment or sexual violence, feelings of shame, fear, emotional distress may be evoked. This can lead to either an unwillingness to participate or disclose any instances of sexual violence.

This fear in disclosing may also be exacerbated when there is:

Interestingly, the presence of an interviewer itself could have a positive or negative effect on disclosure rates. When the interviewer is well trained, experienced in the topic and the language used, they can be a key figure in ensuring the respondent is supported appropriately when disclosing painful experiences in an interview setting. However, the converse is true, when an interviewer, by asking the question to a respondent, can induce social desirability where the respondent gives an answer that would be more socially acceptable than the truth.

To limit under-reporting these were the aspects highlighted when designing the survey:

The topic of sexual violence is an emotive and sensitive one. Collecting clear and objective data on this topic is challenging due to the personal reaction to the topic and the difficulty in terms of categorising of experiences. For a survey on lifetime prevalence, recalling previous experiences can be deeply affecting. In addition, the nature of these experiences and the differing personal interpretations of consent may mean that people are not consciously aware that they have had these types of experiences.

The design of the survey meant that the sensitive questions were solely completed through self-completion and facilitated by several modes for the respondent to complete. While this limited a dynamic assessment of respondent distress throughout the survey, there were many advantages to this, for example, removing an interviewer from the interview in the case of the online and paper modes, giving a respondent control as to when and where they want to complete the survey. These can, in themselves, reduce distress.

An overview of the ways in which managing respondent distress was addressed for the SVS is given below:

Learn about our data and confidentiality safeguards, and the steps we take to produce statistics that can be trusted by all.